Major Changes in U.S. Patent Law

On September 16, 2011, U.S. President Obama signed into law the biggest set of changes to U.S. patent law since 1952. To see a copy of the changes, click here. Much has been written about the changes, and much will continue to be written. Rather than repeating what so many others have said already, I will reserve this space for items that would be of particular interest to Israeli businesses. I will report new developments as I become aware of them.

Regarding the Best Mode:

A Strange Invention for an Even Stranger Law

First, I introduce an invention, a bit strange and totally hypothetical. The invention is circuitry to add to an ordinary car battery to improve its performance (holds more of charge, holds it longer, etc.).

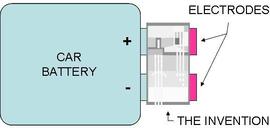

The following figure displays the circuitry in use:

The following figure displays the circuitry in use:

The circuitry attaches to the car battery’s electrodes, and then additional electrodes attach to the circuitry to enable connection to the car’s electrical system.

The Israeli inventor only needs to provide a schematic of the circuitry to an average skilled electrical engineer to enable that engineer to design for manufacture versions of the invention to increase the battery’s performance 15 to 20 percent. No one is aware of this circuitry ever existing in the past, and it is far from obvious. This invention appears to be a strong candidate for patent protection.

Here’s the strange (and also fictitious) part: the inventor has also discovered that, if he manufactures the circuitry at an elevation that is within five meters of sea level, without the presence of sea air (the salt content), the battery’s performance increases 25 to 30 percent, and the costs of manufacturing the circuitry decrease by 10 percent.

The circuitry would be easy to reverse engineer to achieve the benefit of the increased performance of 15 to 20 percent. One only needs to purchase the product and then to provide it to the right electrical engineer. Thus, the inventor realizes that he needs patent protection to prevent competitors from doing just that.

However, as this hypothetical goes, it would be very difficult for anyone to realize that manufacturing the circuitry within five meters of sea level would significantly increase the battery’s performance and decrease the manufacturing costs. Without giving the secret away, the inventor can set up a factory on land between Ma'aleh Adumim and the Dead Sea at the right elevation, or (if your “preferences” differ) on land near the Kinneret that is also of suitable elevation.

Think about it. Although the inventor could not hide a factory in these areas, it would be very unlikely that competitors would check the elevation nor think that it could matter. It is also unlikely that a competitor’s factory would by chance be located as such elevation. Even if it were, it would likely be near an ocean, so the sea air would prevent the competitor from achieving the additional advantages. (I’m not aware of many manufacturing plants built near Death Valley in California.)

Thus, the inventor considers maintaining as a trade secret the best elevation for manufacturing the circuitry while simultaneously applying for a patent. With such a combination of patent and trade secret protection, he could not only require license fees from competitors, but he could also compete with them at lower costs.

He can do this in Israel. That is, he can apply for a patent by disclosing the schematic of the circuitry. That way, he satisfies the requirement of enabling a skilled engineer to exploit the invention. That is an applicant’s obligation in return for a government-protected temporary monopoly, a patent. The Israeli patentee may also keep the best-elevation aspect a trade secret.

The inventor does not have this option for a U.S. patent. U.S. law includes a “best mode” requirement to qualify for patentability. That is, the inventor must disclose the best way he subjectively believes to make and use the invention. Accordingly, the inventor must disclose the best-elevation aspect along with the circuit schematic, if he wants a U.S. patent.

Some readers are sure to ask, “How would the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) know if the inventor concealed the best-elevation aspect?” The answer is simple – but unfortunate: the PTO may very well not know. How could it? Worse yet, there may be quite a few patents improperly granted because of prosecution misconduct by applicants and/or their attorneys concealing the best mode. (Those attorneys, if there are any, should be disciplined by the PTO, if not disbarred.)

I discussed a strange invention. Here’s where I discuss an even stranger law. It concerns a patent holder who sues a competitor in the U.S. for patent infringement. The law also concerns the accused infringer.

When sued for patent infringement in the U.S., the accused may demand to see the internal records of the patent holder. The accused may depose the patent holder’s company employees, also. The court will enforce this demand. It then becomes very hard to conceal relevant facts, such as the competitive advantage of locating a circuit factory away from the ocean and at an elevation within five meters of sea level.

For a long time, the U.S. law permitted one accused of patent infringement to avoid liability if it could be shown that the inventors or their attorneys concealed the best mode. Sometimes, it was difficult to determine what the inventors subjectively believed at the time the patent application was filed, and the relevant inquiries could be expensive, as it often the case with patent litigation. Nonetheless, such a provision in the law prevented profiting through misconduct/fraud.

This law changed on September 16, 2011. That is, in the words of the statute, “the failure to disclose the best mode shall not be a basis on which any claim of a patent may be canceled or held invalid or otherwise unenforceable.”

However (and here’s the really strange part), it is still a requirement to disclose the best mode when applying for a patent. That is, the inventor described above may apply for a patent first in Israel and then file within a year in the U.S. claiming priority to the first filing date. He could keep the best-elevation aspect a trade secret without violating Israeli law. However, he would be required to disclose the best-elevation aspect to the U.S. patent examiner.

If the inventor did not disclose to the U.S. patent examiner the best-elevation aspect (again, any U.S. patent attorney advising such should be disciplined), he may receive the patent anyway. The patent examiner would probably have no way of knowing that the best mode was concealed.

Now imagine the inventor suing a competitor in the U.S. for patent infringement and the infringer’s attorneys discovering that the best mode was concealed. The concealment will not shield the competitor from liability. The law seemingly permits an inventor to profit from fraud on the PTO.

It is very puzzling why the U.S. would enact a law that is so easy to violate with seemingly no penalty. This is by no means a situation in which a law slipped by the legislature without anyone considering how seemingly easy it would be to reward fraud. I have discussed this with many colleagues, and no one knows why the law passed. Some have speculated that it will not last. I tend to agree. Certainly, I do not want to be the attorney to argue in court, “Yes, your honor, my client indeed violated the law by consciously concealing the best mode. However, the law clearly states that the infringer cannot avoid liability as a result.” Judges can be creative, and I would not want to test them by seeing whether they would permit a fraud to be rewarded.

My comment for now (which on this post cannot be construed as formal legal advice) is, until further notice, to continue to disclose the best mode when filing for a patent application in the U.S. Just continue to regard it as the price to pay for a temporary monopoly.

The Israeli inventor only needs to provide a schematic of the circuitry to an average skilled electrical engineer to enable that engineer to design for manufacture versions of the invention to increase the battery’s performance 15 to 20 percent. No one is aware of this circuitry ever existing in the past, and it is far from obvious. This invention appears to be a strong candidate for patent protection.

Here’s the strange (and also fictitious) part: the inventor has also discovered that, if he manufactures the circuitry at an elevation that is within five meters of sea level, without the presence of sea air (the salt content), the battery’s performance increases 25 to 30 percent, and the costs of manufacturing the circuitry decrease by 10 percent.

The circuitry would be easy to reverse engineer to achieve the benefit of the increased performance of 15 to 20 percent. One only needs to purchase the product and then to provide it to the right electrical engineer. Thus, the inventor realizes that he needs patent protection to prevent competitors from doing just that.

However, as this hypothetical goes, it would be very difficult for anyone to realize that manufacturing the circuitry within five meters of sea level would significantly increase the battery’s performance and decrease the manufacturing costs. Without giving the secret away, the inventor can set up a factory on land between Ma'aleh Adumim and the Dead Sea at the right elevation, or (if your “preferences” differ) on land near the Kinneret that is also of suitable elevation.

Think about it. Although the inventor could not hide a factory in these areas, it would be very unlikely that competitors would check the elevation nor think that it could matter. It is also unlikely that a competitor’s factory would by chance be located as such elevation. Even if it were, it would likely be near an ocean, so the sea air would prevent the competitor from achieving the additional advantages. (I’m not aware of many manufacturing plants built near Death Valley in California.)

Thus, the inventor considers maintaining as a trade secret the best elevation for manufacturing the circuitry while simultaneously applying for a patent. With such a combination of patent and trade secret protection, he could not only require license fees from competitors, but he could also compete with them at lower costs.

He can do this in Israel. That is, he can apply for a patent by disclosing the schematic of the circuitry. That way, he satisfies the requirement of enabling a skilled engineer to exploit the invention. That is an applicant’s obligation in return for a government-protected temporary monopoly, a patent. The Israeli patentee may also keep the best-elevation aspect a trade secret.

The inventor does not have this option for a U.S. patent. U.S. law includes a “best mode” requirement to qualify for patentability. That is, the inventor must disclose the best way he subjectively believes to make and use the invention. Accordingly, the inventor must disclose the best-elevation aspect along with the circuit schematic, if he wants a U.S. patent.

Some readers are sure to ask, “How would the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) know if the inventor concealed the best-elevation aspect?” The answer is simple – but unfortunate: the PTO may very well not know. How could it? Worse yet, there may be quite a few patents improperly granted because of prosecution misconduct by applicants and/or their attorneys concealing the best mode. (Those attorneys, if there are any, should be disciplined by the PTO, if not disbarred.)

I discussed a strange invention. Here’s where I discuss an even stranger law. It concerns a patent holder who sues a competitor in the U.S. for patent infringement. The law also concerns the accused infringer.

When sued for patent infringement in the U.S., the accused may demand to see the internal records of the patent holder. The accused may depose the patent holder’s company employees, also. The court will enforce this demand. It then becomes very hard to conceal relevant facts, such as the competitive advantage of locating a circuit factory away from the ocean and at an elevation within five meters of sea level.

For a long time, the U.S. law permitted one accused of patent infringement to avoid liability if it could be shown that the inventors or their attorneys concealed the best mode. Sometimes, it was difficult to determine what the inventors subjectively believed at the time the patent application was filed, and the relevant inquiries could be expensive, as it often the case with patent litigation. Nonetheless, such a provision in the law prevented profiting through misconduct/fraud.

This law changed on September 16, 2011. That is, in the words of the statute, “the failure to disclose the best mode shall not be a basis on which any claim of a patent may be canceled or held invalid or otherwise unenforceable.”

However (and here’s the really strange part), it is still a requirement to disclose the best mode when applying for a patent. That is, the inventor described above may apply for a patent first in Israel and then file within a year in the U.S. claiming priority to the first filing date. He could keep the best-elevation aspect a trade secret without violating Israeli law. However, he would be required to disclose the best-elevation aspect to the U.S. patent examiner.

If the inventor did not disclose to the U.S. patent examiner the best-elevation aspect (again, any U.S. patent attorney advising such should be disciplined), he may receive the patent anyway. The patent examiner would probably have no way of knowing that the best mode was concealed.

Now imagine the inventor suing a competitor in the U.S. for patent infringement and the infringer’s attorneys discovering that the best mode was concealed. The concealment will not shield the competitor from liability. The law seemingly permits an inventor to profit from fraud on the PTO.

It is very puzzling why the U.S. would enact a law that is so easy to violate with seemingly no penalty. This is by no means a situation in which a law slipped by the legislature without anyone considering how seemingly easy it would be to reward fraud. I have discussed this with many colleagues, and no one knows why the law passed. Some have speculated that it will not last. I tend to agree. Certainly, I do not want to be the attorney to argue in court, “Yes, your honor, my client indeed violated the law by consciously concealing the best mode. However, the law clearly states that the infringer cannot avoid liability as a result.” Judges can be creative, and I would not want to test them by seeing whether they would permit a fraud to be rewarded.

My comment for now (which on this post cannot be construed as formal legal advice) is, until further notice, to continue to disclose the best mode when filing for a patent application in the U.S. Just continue to regard it as the price to pay for a temporary monopoly.

If you would like to receive informative Articles and Alerts like this emailed to you, click here.

Disclaimer: The above does not constitute legal advice nor create an attorney/client relationship. For legal advice and an attorney/client relationship, you are welcome to contact me.

Disclaimer: The above does not constitute legal advice nor create an attorney/client relationship. For legal advice and an attorney/client relationship, you are welcome to contact me.